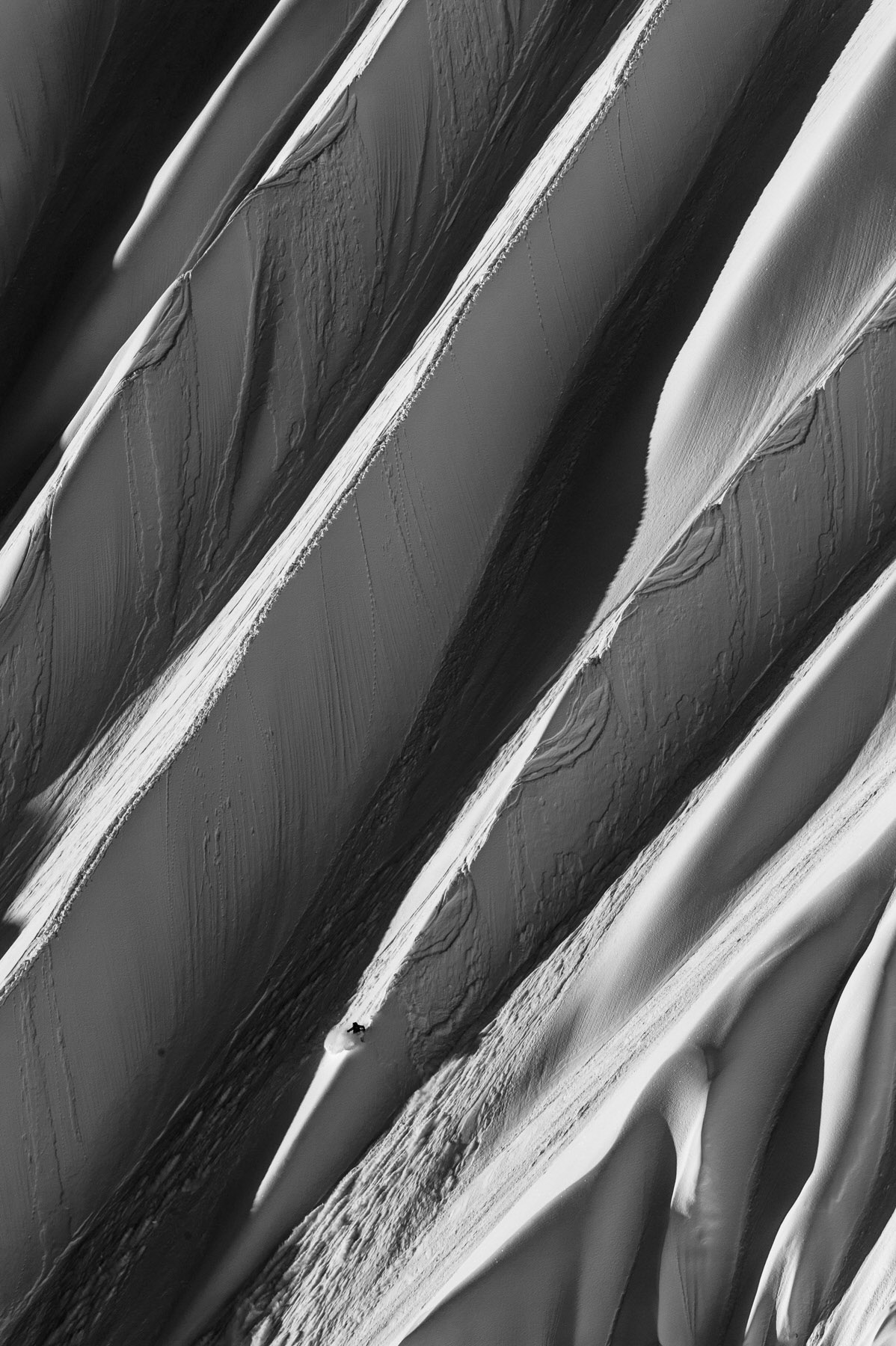

Skiing in Front of a Solar Eclipse: A Once in a Lifetime Shot by Reuben Krabbe

In 2015, Reuben Krabbe and a team of skiers traveled to the Arctic Circle to ski remote mountains and shoot a total solar eclipse while doing so. Battling extreme weather conditions, they made the long, arduous trek to Svalbard, one of only two places in the world where the total solar eclipse could be seen. The journey was incredibly difficult and stressful, but the experience and imagery they were able to capture was extraordinary.

In our interview with Reuben, we talk about how he became one of the world’s leading ski and mountain bike photographers; what it was like to capture the impossible shot that became a massive success; and life after ‘Eclipse’.

Can you tell us how you started out as a photographer?

RK: I started by ending up with two hobbies that, sort of, overlapped and then formed each other. I started photography just for fun while I was a mountain biker and a skier. I see nature, and you just need something to point the camera at, so you point it at what you’re interested in and that was, for me, these adventure sports. Then, at the end of high school, I had developed a pretty expensive hobby and loved the idea of doing actions sports photography, but had all of the phobias that everyone would be familiar with, like being told that no one makes it and that it’s not necessarily a financially sound future.

I don’t think anyone should have any Illusions about that. It’s definitely a rare thing that you get the action sports photographer thing to actually work out. There are a lot of people who get to do it as an adventurous hobby, but not necessarily get to call it a career. So my parents told me that no matter what, if I was doing photography or if I was doing something else, I should be going to school for at least a year after that and get a little bit of a better brain for whatever it is that I am trying. So I did one year of photography school followed by one semester of some business education that wasn’t specifically centered around photography; it was just a general self-employment one.

And then, I made the glamorous move into a Honda Odyssey minivan and this is before everyone had this nostalgic love of van life. This was just living in a bad soccer mom van and trying to cruise around BC and meet people, meet skiers, and try to create images and learn and experiment. By that time I had a couple of clients in Calgary, but I kept on replying from the road saying, “Hey, I’m on the road in BC,” and they’re like, “Do you even live here anymore?” I realized I should actually just be moving to where I wanted to be sooner than later and since then I’ve called the Sea to Sky area my home for seven years and have been doing photography as my sole source of income for seven years as well.

Did you have a specific moment where you actually considered yourself a photographer?

RK: I think you get a lot of small versions of those things. As a photographer, you don’t necessarily have one pivotal moment and part of what I figured out while going to business school and trying to strategize how I would launch my business is trying to get into some of the photography competitions that run in the ski and mountain bike communities. These competitions aren’t just submit images that you’ve shot before; they’re competitions where you shoot for three days and create a slideshow in a short amount of time. It forces you to get extremely creative because you’re trying to be as divergent as possible.

And through several of these competitions, they started to reinforce this idea that, “Yeah, I can do this. I can go up against someone who’s been doing this for 10 years and create imagery that seems to hold its own.” Those were sort of my big moments of, “Okay, I think I’m doing this. I think this is actually working.”

Are there any photographers, other people in the industry, that inspire you the most or have influenced your work?

RK: Jordan Manley would be one of my main inspirations. He’s from North Vancouver and did a lot of action sports photography and really drove creative revolution in this genre. Then there’s an old school portrait photographer who you’d recognize his images of Salvador Dali and old celebrities from maybe the 60s or so. His name is Philippe Halsman. He did a lot of really inventive trick photography with analog cameras that inspired me a lot to try to re-envision the way that you can use a camera. And then a skateboard photographer named French Fred. He does a bunch of really fascinating shadow play work in all the stuff that he does in cities and skateboarding, concrete kind of atmospheres.

You do a lot of ski shoots and you’re up on mountains a lot of the time. Some of these places that you’re traveling to are crazy. Can you tell us what goes into getting the shot? The preparation, getting to the location, setting up.

RK: Yeah. A lot of projects will either be motivated by a destination, or by a concept that I’m trying to capture, or a specific landscape or environment. So I’m trying to find the biggest coastal trees to shoot in where you’ve got massive old growth trees. If I’m trying to figure out where you can go do that or just ski some very narrow shoot somewhere absurd, then you have these objectives.

Photography actually takes the backseat through most of the planning and projects. It’s more about conversation around which athletes do you think can fit that project, talking about what kind of weather pattern is going to be the right one, be out in that area, staying informed on the avalanche conditions which is, for the people who don’t travel in the backcountry, it’s like a constantly building layer cake of all the different weather that’s happened over the course of the year, and certain weather patterns create dangerous relationships between the different layers. And we’ll have to try to make sure we manage that risk and find a time that there is going to be less risk that the mountain tries to kill you.

And then, you just get to go on this big long trip or even short, a day maybe near a ski resort backcountry, not too far away, and go shoot these things. Sometimes, that will just be me standing around on an opposing ridge with a long lens where I’m removed from a lot of the danger, or other times, I’m on slopes with the athlete doing the same skiing that the athlete is doing and trying to shoot part way down the slope. And sometimes, I’ll have to anchor myself to the wall. Whatever it is, it becomes very varied on what kind of tools you need for each different thing.

How much are you traveling then? How much are you doing in BC and how much are you traveling to shoot different locations?

RK: I’ve been trying to pare down my travel a lot in how often I get onto an airplane. I don’t talk about it at times because it’s stuff that I’m still working through, but the environmental cost of action sports photography is really quite crazy. And for everyone who specifically concentrates on snow, excessive travel is really like biting the hand that feeds you, to be jumping on airplanes all of the time. So after doing more and more research and understanding those things, I’ve been trying to figure out how to be able to shoot things in a way that I think is more sustainable and something that I can be more proud of.

I don’t have reservations about the trips that I’ve done, it’s just that the very elective travel that we do, stuff that’s really not for anything other than recreation, I think we need to exercise moderation or intentional use of those things. Right now, I think we still celebrate the lifestyle of constant travel. So ways that I’ll try to do that is just sign on to less international travel or less air flight travel. Also, when I do go overseas, I’ll actually spend more time there, that I’m not on an assignment. I’ll spend my vacation time for the year in a place where an assignment sends me and those kinds of things pare it down.

This year I traveled a bunch within BC. I went and did one trip to Japan to go skiing there. I think that everyone knows an Instagram feed is misleading, but mine, I’ll be posting stuff from every different year of my life constantly. So at any point, I’m posting from Norway, Israel, Japan, Alaska, or British Columbia, so it looks like I’m moving around a ton, but I’m not actually on airplanes too often anymore.

What’s your favorite photo you’ve ever captured and why?

RK: I have one photo of my own on my wall that I really like. It’s just a blurry mix of whites, grays, blues, and blacks, a long exposure of me panning across the lake in BC where I created this cool surrealist image. I still like that one and I think I might like it long enough to have it on my wall for a decade.

I don’t end up liking too much of the action photography that I do. Or at least I like what it is, but I have so much attached to each one of those photos that I see where I was standing, the techniques I was using, the shutter speed, all of this other stuff. I like photography that transports you. I can’t quite get transported by something where I know the magician’s tricks that I was putting into it.

I still enjoy making the photography that I do, but most of it isn’t something that I’m very interested in looking at myself.

As far as creativity goes and photos that you can look at afterwards and be really proud of, what kind of photography would you be shooting if you could be?

RK: I like treating photography like collecting hockey cards. Once I’ve done something and have one version of that, I’m no longer interested in getting another one and I’m looking at something else. So for me, I’ll always, on an experience level, enjoy being in the mountains and shooting photos of whatever it is that I’m doing, but the stuff that I find interesting is doing something that’s hard, requires learning, research, being vulnerable to failure, something that’s difficult.

Do you have any particular habits that are part of how you begin your creative process?

RK: I try to. It’s hard to describe I guess. I’m mostly trying to remix concepts from other places into the work that I do all of the time. So I end up remixing astrophotography things or nerdy camera tricks because I find it super interesting how you can work with lights and perception to create something that’s new and different. I end up finding things that I find interesting in books, or in YouTube videos, or wherever else. And then I remix those strange, different concepts into the photography that I do.

I think what ultimately makes the most interesting photographers is almost everything other than what their relationship to photography is. A good example is Paul Nicklen. He’s a National Geographic photographer who does a bunch of stuff with oceans and the Arctic. But he grew up in the Arctic and became a biologist and was working in the field, and then started using a camera. So what’s really interesting is that he’s shooting things fully informed as a biologist of what’s happening in climate change and that informs his photography. It’s not that he’s taking the absolute best aperture that a photographer could take in that scenario. The other interests of the photographer are the things that actually make them really interesting.

Do you have a favorite quote that really gets you fired up?

RK: It changes from time to time. I used to, sort of cynically, say, “I like to keep moderation to moderation,” and really go for things and get really invested in them rather than just doing different things at a tertiary level. It makes me think about diving deep, but I don’t really have a motivational quote so much.

What book would you recommend any creative person read?

RK: There is a composition and design book called The Photographer’s Eye, and that was super useful for me to develop how I shot compositions.

I don’t read much fiction. Pretty much anything by Hemingway I find fascinating because he worked so indirectly through language, through this understated style. And I think that if you draw parallels to photography, that could be interesting as well. You know, if you’re shooting the subject, you need to shoot everything around the subject so the subject can actually become more interesting.

What do you do when you hit a wall during your creative process?

RK: When you have a midlife crisis, you buy a motorbike! I’ve already had a couple of those. Amongst my friends, I almost joke about it now that I have an end-of-ski season depressive streak. I’ve gotten a lot better at managing it now, but I used to get really bummed out at the end of every season, just being like, “Oh, I should have done more. I only like 10 photographs from this entire season. This sucks. I’m a fraud,” and go down that deep dark hole.

Then, after “Eclipse,” because our project was so widely received and so broadly seen, and the movie was such a crazy thing to watch, I don’t know if any project I’ll ever do could be the same, have the same draw.

I have a couple of different things that end up being my mental medications for that. I try to be really grateful for the fact that I have experienced things that are so cool, things that I don’t know if I’ll experience something as amazing again. It’s rare to be able to have that kind of thing. I try to make sure that I don’t try to get out of my dark creative pattern by using more thinking. I need to get out into nature and just do the stuff that I know I love and that actually brings me back to stability. If I spend my day sitting around at a computer, editing and trying to think of something that’s going to be better than anything I’ve ever done, that is a sure bet to not to come up with any good ideas and to get pretty depressed.

Can you tell us about your experience with Eclipse? It was such an amazing project. How did it come about and what were some of the after-effects?

RK: After the American eclipse last year, it seemed obvious that photographers would try to reinvent and use an eclipse as a creative tool for their photography. But prior to this last one, that hadn’t really been done. Through a lot of the concept remixing and brainstorming that I do in my photography, I had figured out that trying to ski during one of these eclipses would be a really, really mind-blowing visual thing to do. And I pitched that to a ski company, Salomon. I was trying to tell them, “Hey, we should just go ski and do stuff in front of it. It will be super interesting.” I pitched that to them as my secret way of saying, “Hey, I’m going to get to go shoot this if they say yes to it.”

But they called my bluff and started filming the project, not telling me that it was about this journey that I was on to shoot a photo during the solar eclipse. And then, they ended up producing a half an hour movie about this journey of myself and a group of skiers trying to create imagery around this experience. That movie and that photograph were seen more than anything else I’ve ever created. I definitely have also noticed that they were crazy influential for my career as well. Those images have staying power that everything else I’ve created has pretty much paled in comparison.

It was utterly surreal because I went from basically one of the most intense feelings of stress and being a bit lonely on the project, feeling like I was trying super hard and potentially still going to fail at creating something, and it was making the other skiers’ experience of the trip worse. So I was very stressed about this entire thing and felt like I was in the center of it, making the decisions about where we should ski and how things should work. Even on the morning of the eclipse, we still weren’t confident we would create anything of interest and then we ended up getting extremely lucky.

The eclipse is such a fascinating thing to see because it almost resonates on a subconscious level. You don’t ever think consciously that the sun is in the sky and that’s normal because it’s so normal that you never think about it. It’s like experiencing gravity. It happens so much that it’s not even a thought. But when the sun disappears and it looks like a black hole in the sky, everything in your human body just freaks out because everything is wrong. Everything is really aesthetic and beautiful during that moment as well. It’s very stimulating, but you’re just freaking out on every level because it is such a surreal experience. So I went from this really dark feeling of stress to capturing images during this moment that were as good or better than I thought I could create, and it felt like an amazing, amazing mood swing.

And then, with the hype afterwards and the success of it, how did that hit you? Did you expect it to do as well as it did?

RK: Well, it was sort of funny. We all thought we had something special, but we also didn’t know if it was just a thing where like, the parents are too proud of their own kid. We all knew that the experience was profound for us, but we didn’t know if that was going to translate in any way. So all the way up until the actual release and the premiere, the Salomon crew had shown it to media and marketing people trying to work on the story and make it better, but we still hadn’t shown it to a public audience to know if people would find this whole thing interesting or if it would just come across as absurd, scientific, and self-indulgent all wrapped into one big burrito.

But then, when people responded really positively at the premiere, it all of a sudden was like, “Okay, that was justified. This whole thing resonates with people; it’s really cool.” And since then, it’s still amazing that I’ll receive messages on Instagram or my email saying, “Hey, that project was super inspiring for me. And it helped me chase what I wanted to do.” And that’s something that I didn’t aim to do through the project, but is really amazing to hear.

What are you working on now? What’s next for you?

RK: I’m working on a new version of the celestial skiing remixing stuff. I don’t want to go too far down the hole because I prefer to be successful before calling out what I’m trying to do.

I’ve also just been trying to expand my own experiences beyond photography. For the last two, three years, I’ve been working more on trying to become a better skier and photograph the ski experience from alongside professional athletes. I’m spending more and more time on slopes doing the stuff that skiers are doing, and that’s a difficult and rewarding experience as well, just trying to do stuff that’s scary, and athletic, and interesting. It’s helping me shoot a more personal side of skiing, rather than just this vacant or distant, “Look how crazy these guys are.” I’m trying to capture personality or the experience of being inside their head.

To see more of Reuben’s work, from his awesome aurora borealis shots to fast-paced mountain biking and ski photography, check out his website and Instagram. And, if you haven’t seen the ‘Eclipse’ video yet, you should watch it; it’s a super tense and exciting behind-the-scenes ride following Reuben and the team on their journey.