How Photography Helps a Five-Year-Old Boy with Autism Understand the World

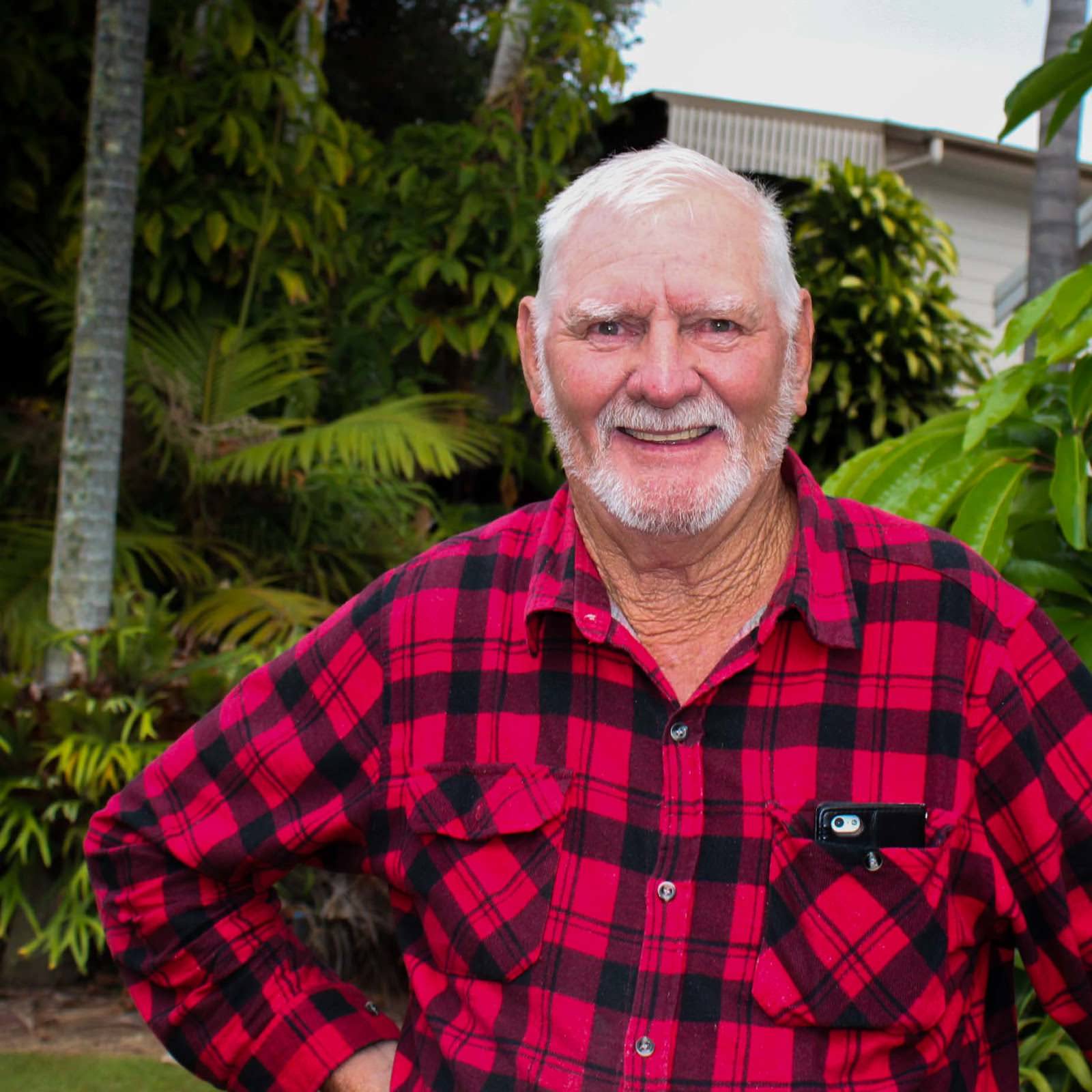

In 2017, Danielle Pritchard brought her son, Max, to a family gathering. He was four. She brought a camera from the high school where she teaches, an entry-level Canon DSLR, which she’d been fiddling with for her art class. Max seemed restless, so she handed him the camera to play with.

Then, something changed in him.

“I gave him the camera, and he was really fascinated by it – and all of a sudden, these kids just swarmed to him,” Pritchard recalls over the phone from her home in Brisbane, Australia. “It gave him a bit of purpose and a sense of belonging, which hadn’t happened before. And it was just relief, I guess, or a lightbulb moment: maybe he needs something between him and the neurotypical world to help him.”

The moment was remarkable because Max is on the autism spectrum. It’s not noticeable when you meet him at first, but he has trouble socializing and controlling his emotions, and gets easily overwhelmed by noise, sights and smells. But with a camera in his hands, Max felt confident. A tactile and technically-minded boy, at that family gathering, he began removing and re-attaching the lens, playing with different settings and explaining its functions to other children.

“It might not have necessarily been 100 percent correct – he may not have been explaining exposure value,” his mom laughs. “But he was saying, ‘This is the lens, it comes off and on,’ and ‘This is how I take a photo.’ He knew how to press the play button. And the kids would say, ‘Take a photo of me!’ So he would take a photo of them.”

Since then, Pritchard and Max have gone on long photo walks, which she’s found has helped him better engage with the outside world. He becomes more curious and talkative, while she uses those moments as conduits to explain things to him: if they spot a boat and he wants to photograph it, she’ll explain what boats are.

This is typical for photographers with autism. According to a 2016 study published in the scientific journal Current Biology, people on the autism spectrum tend to spend more time composing photos than non-autistic people, and they take more photos per session on average, because they spend longer analyzing what they’re looking at.

For Max, photography is as much about world-analysis as it is about social interaction. Shortly after that first revelation at the family gathering, Pritchard took him for a walk around the neighbourhood, where they met a Sikh man with a large maroon turban. Max wanted to take a photo of him. Pritchard explained how he should approach the man to ask to take his photo, which he did.

“He was happy to let Max take his photo,” she says. It turned into a discussion about shadows and lighting. “It just opened communication,” she adds. “That reinforced the idea that Max could use the camera, and the technical side of the camera, to approach people, to talk to people.”

Numerous folks with autism have found similar solace in photography. Sam Parrish-Lyne, a U.K.-based student and budding professional photographer, has written that the technical elements, amount of control and application of knowledge users can exhibit combine to make photography an ideal hobby for people with autism, who often skew toward perfectionism and a technical way of understanding things.

In Michigan, teenage photographer Malcolm Wang echoed those sentiments in a recent news article: “I liked to press buttons on cameras. I like to look at pictures. As a child, I loved to press elevator buttons and when I did chores I enjoyed pressing the dishwasher and washing machine buttons.”

That’s true for Max, too, who’s drawn toward complex SLRs over point-and-shoots. “We have a point-and-shoot, and he kind of liked that it was blue,” his mom laughs. But ultimately, he preferred the SLR. “He liked the fact that he could take the lens off, or push buttons and experiment more.”

The proud mother nurtures Max’s experimental side by taking him to meetings of a local photography club. There, judges will discuss core photographic elements. Pritchard explains these to Max, who does absorb the knowledge, though he doesn’t always apply it in his work.

“The discussions that people have about photography – I think it’s really quite structured,” she says. “You start to talk about depth of field and leading lines… but Max just takes it differently. He doesn’t know any of these terminologies, and he’s talking about it from his perspective.”

Once they’d accumulated a whole library of photos, Pritchard sat down with Max in front of their computer, booted up Adobe Lightroom and started sifting through them. The process is a little brisk, with Pritchard deleting many unusable ones and Max pointing out his favorites.

By April 2018, Pritchard created an Instagram account for Max, adding just a few hashtags and clarifying that all photos and captions were created primarily by Max. In August, when he had just 60 followers, a local reporter at the Australian Broadcasting Corporation heard about his story and wrote about it; now, Max has more than 1,000 followers.

Pritchard is grateful for the attention, mostly because it allows her to spread awareness of early intervention for children with autism. Numerous studies have found that early intervention – specialized programs designed for children under the age of seven, particularly between the ages of two and four, when the brain is most malleable – helps children with autism grow up stably, healthily and with an improved understanding of social cues.

By meeting strangers on the street, Pritchard also gets the opportunity to spread this message personally with other adults. She’s become as much an ambassador for autism awareness as she has for Max’s own development through photography.

“For me, it’s about awareness and early intervention,” she says. “If somebody reads this and says, ‘Oh, maybe I could try something different for my child,’ or, ‘I think my kid’s autistic, maybe I should go and get some help,’ that would be wonderful.”

As for Max? She doesn’t want to pigeonhole him into something he may grow out of. “A lot of people say, ‘Aw, I can see he’s going to be a great photographer!’ And it kind of makes me a bit uneasy, actually. Because I don’t want to push him into something he might not want to do.”

Max is into photography now, and his whole family supports him. But if he grows out of it, Pritchard says, they won’t force him to keep it up. After all, photography is about expression – not about playing by the rules.