A Fun Approach to Product Photography and Composition with Ross Floyd

In e-commerce, there’s one undeniable truth: how a product is visually represented makes the first impression on a potential buyer. In order to make that product irresistible to consumers, the photographer needs to know which elements to draw attention to and how to use effective techniques, like lighting, retouching and compositing to really grab the viewer.

Ross Floyd has been shooting product photography for over seven years, working with a team where he shot for eight hours a day and created about 10,000 images a year himself. His extensive experience has led to him working with some of the biggest furniture manufacturers in the world and pulling off some incredible photoshoots. So, how could we not invite him to share his knowledge and tips in our Ultimate Guide to Product Photography?

Over the past few weeks, PHLEARN has released a couple new Pro Tutorials about product photography – from what makes it different and the tricks you can use to shoot great product photos to how to masterfully retouch and composite images at a pro level. Ross joins Aaron Nace in the studio to show us his approach to product photography and help make it a little more approachable and less daunting for people looking to break into the industry.

Today, we chat with Ross about his emergence in the product photography world, his biggest influences, the weirdest things he’s ever shot, and his favorite projects to date.

Can you describe what it is that you do? How did you get into product photography?

I tell stories of people who make things. And about the objects, and spaces, and experiences they create. That’s the underlying theme of everything that I do.

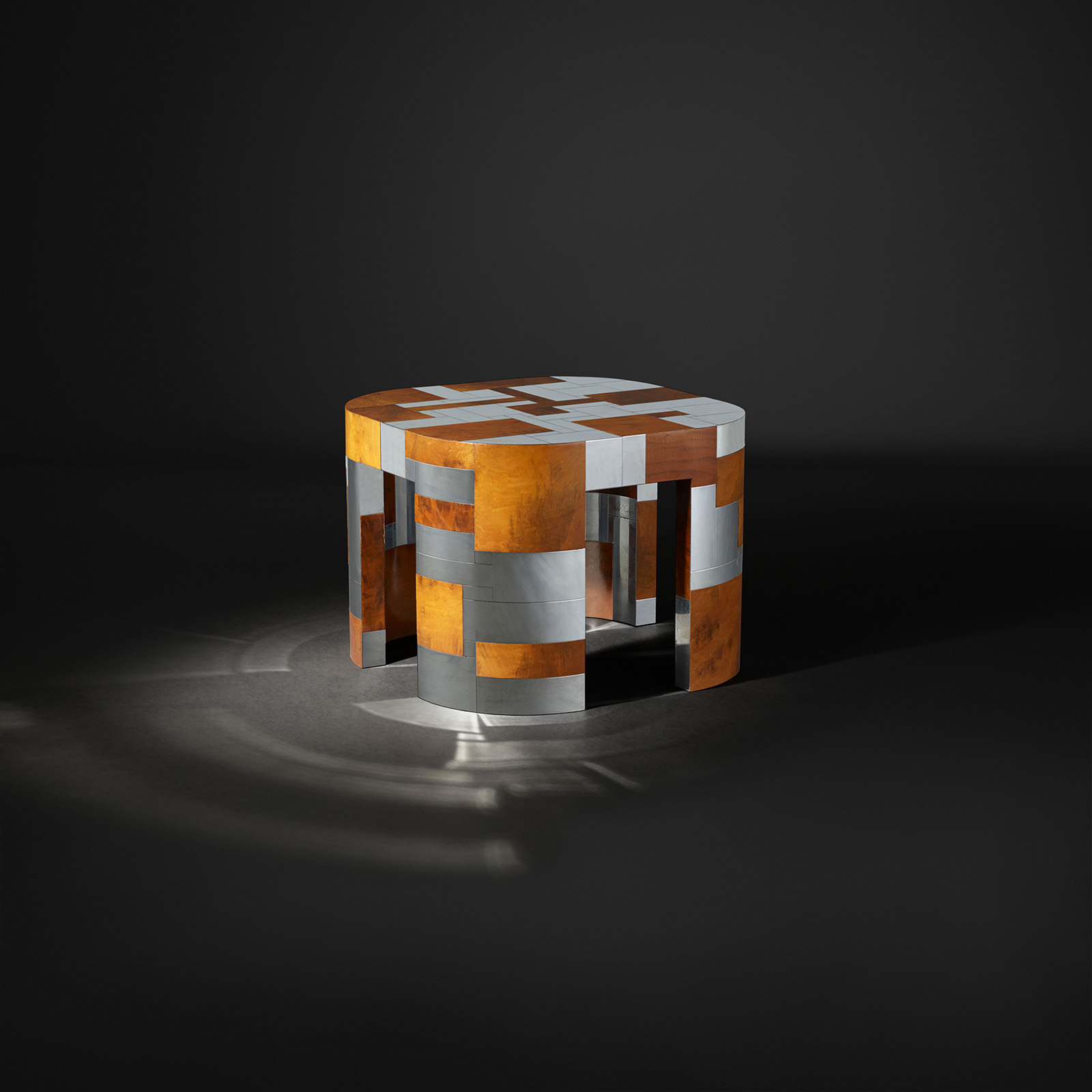

I’ll shoot really high-end furniture one day, then I’ll shoot construction workers putting up a new type of building material the next day. I’m all over the board. But I really have a passion for really high-quality imagery. That’s what most of my clients are drawn to.

I went to school for photography. Actually, my background is in digital printing. I worked for another photographer named Jason Lindsey for about four years and I learned a lot from him. He was a travel and advertising photographer, so we had a lot of challenges. We were on location all the time using generators, and batteries, and things like that, which is really fascinating because that’s kind of what I do now.

After that I moved to Chicago and I got a job working for Wright Auction House. They deal in high-end 20th-century art and furniture, so anything from Eames chairs to Picassos to just random, found objects. Things like a collection of 50 hand-painted cheerleader horns from the 60s. I had to learn how to photograph every material and every different object.

And the caveat about that place was that we weren’t allowed to Photoshop the objects themselves. So we really had to learn how to light the object in the most flattering way. Then we’d hand it off to the retouchers and they would retouch the background and around the object, so that you didn’t present any distractions. I did that for seven years – eight hours a day, every day.

It was like boot camp. And it was a great place to learn. It was a small company, but they did a lot. Over the time I was there, I think we produced over 200 catalogs. Each one has its own look, so we’d have to redesign lighting. And then, sometimes, we’d design and build sets. We would present stuff in new and exciting ways. It was wild.

Were you always interested in product photography?

When I was in school, I was shooting mostly people. My senior year, my thesis was this kind of really goofy diptych. Most of my work then was about my anxiety with relationships and things like that. So, the best one I did was actually a still-life of two plastic skeletons that I had stolen from a science lab.

I had them posed as if they were hugging each other. And then, the next one, I blurred that same image so it looked like a blurry image of people in flesh. It was all about death and this is the end. Visually interesting, but creepy.

There was another one of just two people from the waist down, showing a woman kicking a man in the crotch. It was like a metaphor for some of my other relationship issues. Dating was rough in college.

So that was where still-life started to creep in a little bit. But the real catalyst was Sears was hiring in Chicago, and so was this auction house, and I wanted to apply. I didn’t have any product shots in my portfolio, really, so I went to Kohl’s and bought a bunch of stuff. I bought a blender, a spice rack, and some forks, things like that.

I shot a whole portfolio in a week. Then printed it, interviewed, and had a few job offers. I took the one at the auction house based on that portfolio. Then I was in it and I had to learn fast.

What were some of the initial challenges you faced or biggest things that you learned when transitioning into the new genre?

I learned a whole new skill set. And I feel like it’s made all of my photography better. I feel like – this is going to sound boastful – but I feel like I can light anything. I know that I have the process now where I can light and edit.

I should probably say that I’m a great photographer all the time, but I’m a good editor. I can edit really well. So I can look at something, say that it’s not right, and then figure out what’s missing. Maybe it’s not contrasting enough, not crisp enough. Or, I want to bring more of something out in the image. I know what tools I need to use to do that.

That’s definitely a great skill to have. And I think it’s really important to shoot different genres, as many as possible.

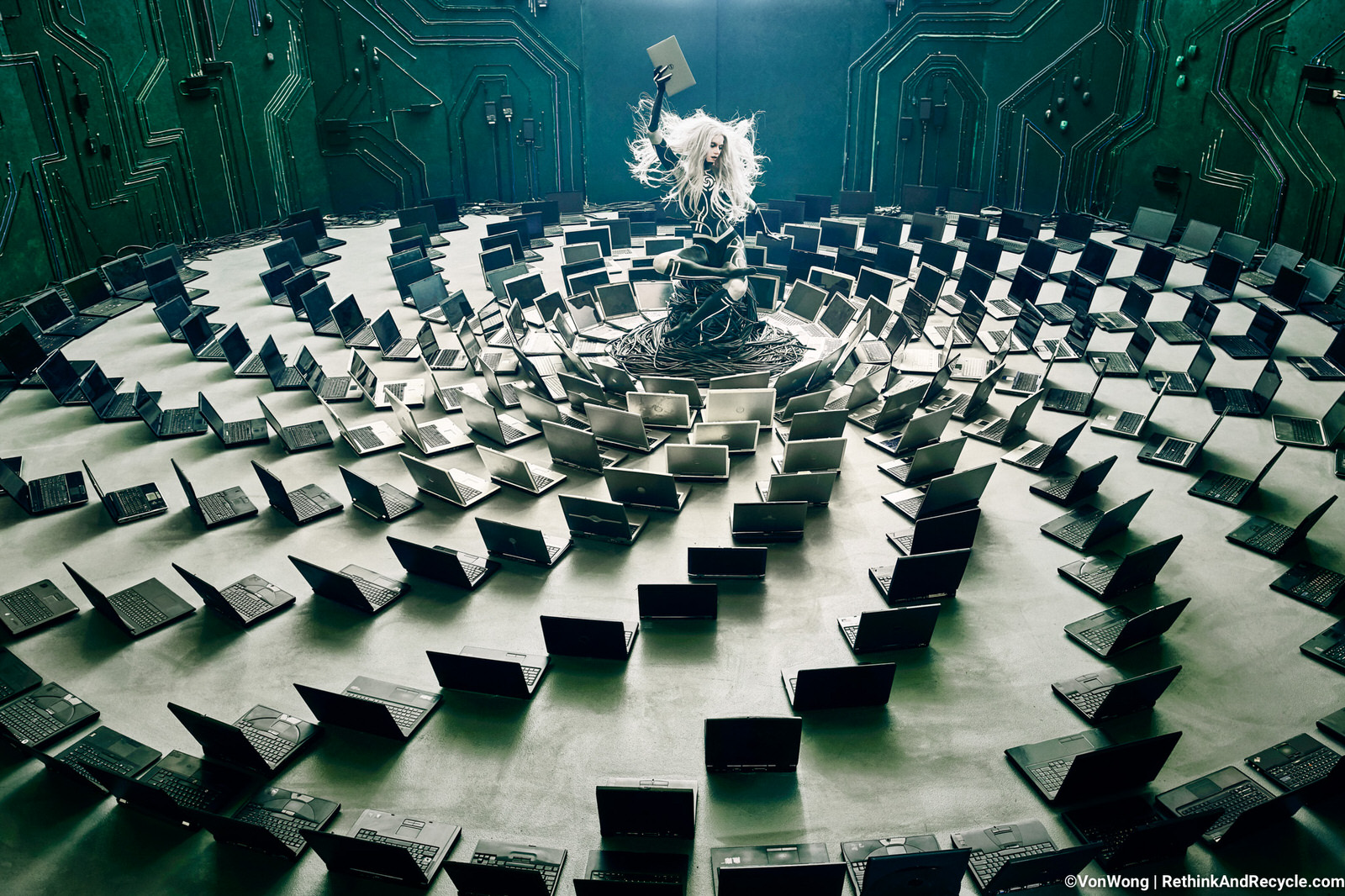

Yeah. For me, it’s mostly commercial-based. It helps you be able to tell the whole story. There’s a really good photographer, his name is Hunter Freeman, and he shoots products, but he also does these super surreal shots. One of my favorites is of this woman holding an iPad in a bathtub and the bathtub has overflowed. It’s like portraiture. It’s like still-life. It’s surreal. All those skills kind of came together for one image.

What’s your typical setup like? Can you tell us about the equipment that you use?

I have a super-scalable setup because it changes. You don’t need the same thing to light a teacup as you need to light a large dining table. For the pro tutorial with Aaron, we shot on Phase One’s new trichromatic 100-megapixel digital back, which I prefer using.

I really like that high-end camera, it just has really, really good images. It’s very expensive though, and I only use it, really, when I’m billing that to a client or it’s appropriate. If I’m not using that, I use a Canon. I have a 5D Mark IV.

And then, I have a few lenses that I tend to use. I can cover most anything with a 24-70 and a 70-200, but I like primes. I tend to run a lot of tilt-shift lenses because you can correct the angles of furniture, the object, make the tabletop feel a little more open so that you show more of the object itself.

I shoot mostly ProPhoto stuff when I can. We used AlienBees when I was shooting with Aaron, just to show that you might have to do a little more color editing or things afterwards, but you can edit light. The reason I use ProPhoto stuff is I know it’s going to work and they give me a lot of battery-operated options that I can add to my kit and rent more things if I need.

When you hear people saying, “Oh, it’s not about the equipment, you can shoot on anything,” what do you say to that?

You can. It’s just going to be more work somewhere else. For me, I like shooting. That’s the process that I’m into. I like relating to the client. I like figuring out problems. But, I’ve never been a big fan of editing things. I think it’s really important to know how so that you can direct that process, but it’s not my favorite thing to do.

So if I spend money or I rent equipment, we’re starting off at a higher baseline. The image is already nice coming out of the camera. Then, I don’t have to spend as much time on the back-end retouching it and making a 35mm shot look like a medium-format shot.

There’s also just some more flexibility that those files offer. The dynamic ranges are pretty close, but the amount of tone that you get – that might disappear with a smaller sensor – is nice. I find that, especially with, wooden tabletops, you can recover a lot more. So I do a lot less work lighting in that process. That sounds like cheating a little bit, but it’s not.

It just has a different feel and presence. People might be like, “Oh, you’re paying that much for a different feel and presence?” And I say, “Well, that’s quality.” When you see a page of my work all up, the impact is pretty strong because there’s a different feel to all those images than you would see on another website.

But, that being said, I do have a little Fujifilm X100F that I love the daylights out of. That thing does things that the medium-format can’t do currently. I can shoot in the dark with it, essentially, and the images have really nice color and are really beautiful. There are certain situations where I’d rather have that thing than this hulking beast.

It’s all compromises. It’s trying to get result by compromise. Some jobs you’re willing to compromise somewhere, and other jobs, there’s no reason to.

When you were starting out, who would you say were your biggest influencers in terms of their style and what inspired you?

When I was in school, I really loved Irving Penn. I really liked his portraiture, and he’s got all these still-life images that I was always really in love with. He had these photos of giant cigarette butts that he would just find in the street, and he would print them super large. It made these tiny things super monumental and crazy. That kind of transformative photography has always been really interesting to me.

Not just making the object look large, but taking something that someone hasn’t seen before, or normally wouldn’t explore, and showing that to people, making it important. To me, that’s a super fun idea.

Even my work at the auction house, a lot of that stuff people only see in museums. Part of the mission was helping to preserve a lot of that stuff.

You must have seen some pretty bizarre and fascinating things.

And I sat in them! I had a whole Instagram series for a while, where I was just sitting in these really expensive chairs and kind of rating them based on comfortability. That stuff was already really nice, but it becomes elevated when you photograph it in a certain way. It becomes more about the idea of what that chair is, or why it was important, in the given time, for whatever reason. You’re telling that story. That’s fun for me, too.

We usually ask the photographers we interview if they have a favorite photo they’ve taken, but let’s get to what we all really want to know… Do you have a favorite chair you’ve ever sat in?

People are probably going to rag on me for this, but there are two. One I don’t have a picture of because it was this rare prototype by a Danish designer named Ib Kofod-Larsen. My friend had it.

Then there’s this lounge chair by Eames that’s very commonly knocked off. It’s the Eames 670 lounge chair. There’s one on my website from above. It’s leather and bent rosewood, and it’s upholstered. It’s, hands-down, the most comfortable chair I’ve ever sat in. You just kind of sink into it. They’re really nice; well, the old ones. The new ones have foam in the cushions, and the old ones are goose down.

That’s super bourgie of me. I did not grow up anywhere near that world. So, it’s weird for me to be saying, “Yeah, I prefer the ones with the goose down!”

And a favorite photo?

There are two. The one that I think gets the most attention – the object is really exceptional – is this giant table, this dining table by George Nakashima that I shot from above. I had to rent a really large studio to shoot that. The guy that owned it was trying to sell it. His name is Whit, he’s an owner of The Exchange International. He was really game. And let me do this kind of crazy thing.

This is a half-million-dollar table. We built this truss support system for the camera with a little sled, and we hung a $60,000 camera above this half-million-dollar table, just so we could shoot down on it. It was a dream for me because the client really understood the vision and why we were doing it.

He was like, “Yes, that’s cool. Let’s do it.” And then, I had to figure out how to do it, how to build a thing that was safe, that we could hang this camera up over the table and not have it drop to either destroy the camera or destroy this priceless thing, essentially.

That table is cool in ways I can’t even describe. It’s the closest thing to having a spiritual experience being in the presence of something. You get that feeling when you’re at the Grand Canyon. This was a man-made object that had that same kind of awe.

The other one was… I got this assignment from a magazine to shoot this very cool foundry in West Chicago, called West Supply. It’s owned by this cool lady named Angie West, who used to be a photographer. They do high-end bronze and glass casting, and they wanted a shot of the entire factory floor. So I had to get up high, and there wasn’t really a place to stand on, but they had a 60-foot ladder.

So I was standing on top of this 60-foot ladder just panning back and forth because I couldn’t get the tripod up there. The whole thing was shaking anyway, so it wouldn’t matter if I had a tripod tied to it. I took a bunch of images to stitch together later as a huge panoramic of these people pouring bronze and polishing things.

It’s this kind of weird Where’s Waldo? image of this giant factory floor. And then we hid the owner in the back corner and she’s constructing a piece of furniture. It was just a fun image to make. It kind of took me back to the film days where you’re like, “I don’t know if this is going to work out, but let’s see what we can do.”

It’s always great when you’re working with a client who sees your vision and lets you have creative freedom. But, when you don’t have that, how do you face that challenge?

One scenario is where they don’t quite understand your vision and they trust you enough to let you do it. That’s super rare. Sometimes I draw things that will help move things in that direction. Or, Pinterest is really useful if I’m going to try and do something. Someone’s probably done it, or something similar, before.

Or you can take two images and say, “Hey, I want to take the lighting from this, but apply the color from this.” Visual research is super important when you’re trying to explain what you want to do with people, whether that’s a client or a model. Any visual thing you can put together is helpful.

I’ve probably lost jobs because I wasn’t articulate enough in explaining what I wanted to do. So, sometimes, I’ll go out and I’ll just shoot what I was going to shoot anyway, just so that next time it comes up, I have work that’s at least close enough to what these people are asking for that I can show them.

What’s your creative process like going into each shoot?

It depends on what you’re shooting. E-commerce is going to be a lot different than shooting a room or shooting interiors. But the same commonality that they have is you are trying to tell a story, and that story might be as simple as this toothbrush is a toothbrush; it’s very toothbrushy. But then, it still has line, color, and shape. You might just have to look at it and break it down.

When you’re photographing a person, you’re like, “Oh, this person has unique eyes, or this person has great hair, or this person has interesting skin.” You’re going to make choices that tell that story a little bit more.

That’s how I like contextualizing all visual art – you’re telling a story no matter what you’re doing. You’re telling the story of color, and texture, and all that stuff, and how is that contributing to your overall image?

Is this room inviting? How do I make it look inviting? Is it arranging the furniture? Is it lighting? I basically just ask, “What am I trying to do here?” Sometimes it’s a simple answer, but a very difficult solution. Like, I need to see that this is actually glass, how do I do that? How do I do that in a white space?

Do you have a favorite quote or a mantra that you say to yourself that gets you fired up?

Yeah, there’s one by Rumi that I’ve been thinking a lot about lately. It’s, “Sell your cleverness and buy bewilderment.” I mean, I’m basically just working so that I can do more cool things.

Then, I have a corny one, too, which has helped me a lot in my business. It’s from the new Rocky movie. The quote is, “One step, one punch, one round at a time.” It’s breaking things down, like, this is what I have to do today. This is what I have to do right now, in this minute.

At some point or another, we all hit a wall. What’s do you do when you have a creative block and how do you get through it?

You just have to make your way out of it. There’s no other way. Some people literally wait to be inspired. But, that’s just not my temperament. I just have to work. I like working. All the stuff I do isn’t always great; some of it is crap.

It’s a bummer, thinking you got this hot idea and… I’ve been doing this Flying Objects series because it’s just fun. I use these high-speed strobes and really fast camera, and I throw shit in the air and it makes these weird little sculptures because you can freeze that motion.

I was super excited. And I was like, “Oh, I’m going to do feathers. It’s going to be totally different than all the metal stuff that I’ve done.” And I could not. They just float everywhere.

I shot over two or three days. I spent way too much time on something that wasn’t working because I wanted it to work so bad. And then, I stopped, and I found a different object. Ideas don’t always work out.

Can you easily walk away from an idea, a concept that you’ve had and tried to make work?

Sometimes you have to. Even when working with clients, you have to sometimes. Maybe they want to take it in a completely different direction than you want to go, and you have to learn to be not as precious with it. I mean, try and get the shot that you want, but, at the end of the day, some of those people are paying your bills, or most of them are, and you have to get what they want.

But, personal things are a little harder to walk away from, I think. That feather shot still kind of bothers me a little bit. But, what am I going to do, right? Maybe in 10 years, I can make that image. That’s kind of the adventure. Maybe I’m just not ready to make that image – yet.

To see more of Ross’ work (and some of the best chairs he’s ever sat in!), visit his website and follow him on Instagram. And, for anyone interested in learning the ins and outs of creating professional product photography, be sure to check out the Ultimate Guide to Product Photography Tutorial.