Finding Work and Truth on the Road

On Working

When I was 11 years old, my mother gave me a book called Working, by Studs Terkel. It catalogued hundreds of interviews with people all over the United States, asking them about their jobs and how they felt about what they did. People were honest and forthright. It had none of the sheen of today’s social media friendly personal narratives. This was raw and exposed and I fell in love with these portraits of real people with real feelings and I thought, “I too will grow up and become a real person.”

That same year I got two other things: a camera and my first photography job. I was a paperboy. At 5:30 a.m., I would get two stacks delivered to my driveway: one was the news and the other was advertisements. I would put them together, wrap it with a rubber band and stick it in my shoulder bag. The first day I tried to ride my bike with a full shoulder bag and couldn’t do it. I stood there and cried. Gathered myself and thought about it. Then I emptied half of it, delivered what I had and came back for the rest. It was inefficient and I hated it, but according to the book, this was work. And as promised, it came with more than a paycheck – it made me feel like I was becoming someone.

This push to define myself through my work went on and on. I worked through college, and then spent the next 30 years pedaling forward, up the ranks of marketing agencies as an Art Director, a Creative Director and, eventually, Chief Creative Officer. Then one day, only two weeks before my 50th birthday, I was fired. This happens in marketing; one day you’re in, the next day you’re out. It’s not personal. Well, it’s all personal until they let you go, then it’s not personal.

That day I went down to the beach. It was raining. I stood in it and looked out at the ocean. For the first time in almost 40 years I was without a job to define me or to be my portrait. I would need to figure out what was next for me. Instead of feeling scared, I felt excited. I felt… 11.

Remember that camera I got? Well, I’d always kept it close. Over the years, the photography had taken on its own life – a parallel one to the career. Many had said that it was my “true calling.” Was it? Without the outside structure to hand me my assignments, I decided to make one up for myself.

In my mind, the state of working in America had changed – for me, for America. It was more of a feeling than anything else. By all counts, our low unemployment rates seemed to paint a picture of a country with its head down, working hard. But I sensed something else. And this notion gave me an idea. What if I went and found out? A journey across the U.S. that would perhaps reveal the state of work in the country and also, maybe, paint a roadmap for me of what’s next.

I pitched the concept (“America at Work”) to a publisher who helped me organize and finance it. After a month of planning, I was packing up my car and saying goodbye to my family and going to find out.

On the Road

Getting a job and doing a job are different things. Getting a job is one kind of stress, but doing it gets deep in the psyche. Within the work you come to know your own limits, what you can handle, what you can’t. Those limits and boundaries tend to become the things that define you and your sense of worth.

On the road, I quickly discovered how hard this job was going to be – questions seemed to fly in the car as often as bugs flew into the windshield. Where would I stay? How would I find people to talk to? How would I photograph them? How would I get them to talk openly and honestly about their jobs? Not to mention the physical tax of driving for long stretches of time in 100+ degree heat, across tiring landscapes.

How did I figure it out? I don’t know, I just did. My mind was on fire and I just learned it. I learned that social media is a powerful resource for making connections. I learned how to look at the trip as both a large circle and a series of small legs and to make decisions based on both. I learned how to book hotels on a nightly basis. How to eat healthy in convenience stores. I learned how to get interviews in almost any setting. How to ask questions, but more importantly how to listen to the answers and how to ask delving follow-up questions. And I figured out exactly which cameras, lenses and settings worked best for me to get great shots (and video) quickly and effectively.

The first week, I was a stressed out mess. The last week I was working out in the mornings and cruising confidently from one city to another. As it turned out, little had really changed since I was 11. You pack the bags, get on the bike and see how much you can carry.

On Looking Back

The happiest workers I met across the U.S. were the ones whose work seamlessly intertwined with their communities. From the museum host at the Jazz History Museum in Kansas City to the bootmaker in Detroit to the framer in Los Angeles to the organic farmers in Michigan, the best parts of all of their jobs were the interactions with the people who lived around them; the museum visitors, the veteran employees and customers whose needs they met, and the discussions that ensued. “How are you?” “How’s the arthritis?” “You know the hot dog festival is next week.”

In large, most people do not reflect on what work means. The cleanest answer to the question, “How do you like your job?” was from a prison guard who looked at me quizzically and simply said, “It’s my job.” The meaning comes not from thinking about it, but from walking forward and doing it. And the hardest part of the job? When there is lack of community, or a community breaks down. I asked a chairman of a big marketing firm in Chicago what the worst part of his job was and he said, “When people you’ve worked with for a long time leave.”

The premise I embarked with was that work had completely changed, but when it was all said and done, that seemed only half true. Yes, there are new models, paradigms, technologies and disruptions – that’s all happening. Even the grain farmer in Iowa uses GPS and has a self-driving tractor. But what hasn’t changed is the value of human connections. That is as alive as ever. That’s work on the outside. There is also work on the inside and I learned about that, too.

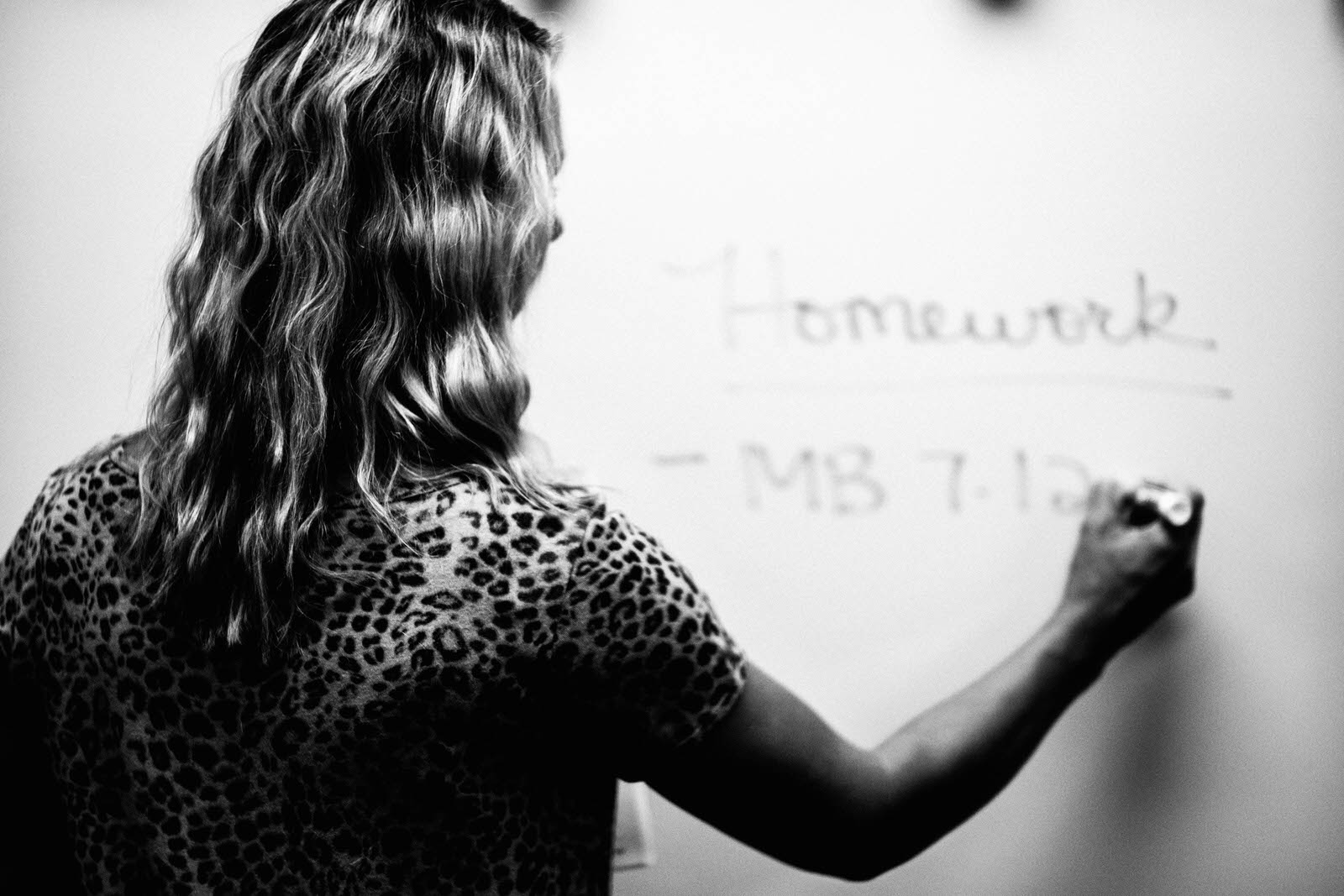

Anastasia is a whitewater river guide in Santa Fe, New Mexico. It’s one of many jobs she’s put together for herself. And she’s also an avid gamer. And she’s taking science classes! I asked her specifically about the river rafting. What is that like?

Anastasia proceeded to describe to me the art of guiding a raft by having a paddle in the water. You feel the river through the paddle. The river is a massive force, but when you get good at the job, you can navigate it by knowing it better and perfecting these little moves.

In the last stretch of land between Colorado and California I was putting the whole trip into some perspective. I thought back on all the interviews. The welder and the waitress. The teacher and the tour guide. And I kept coming back to that river. So, here’s what I think:

We have an instinct to work. It is a force that pushes us to contribute and be a useful part of a community. And that force is the river. The raft, our circle of influence. The paddle, our craft. And we paddle and paddle until we get better at it.

Looking Forward

As for me, my paddle had fallen in the water. It was gone. And now I didn’t want it back. Not that one. But the river, the force, it still flows inside me. Like it does in you. In all of us.

I think I made a mistake at 11 years old. When I read Working, I thought I was learning how to get a job, but I was actually learning about journalism. And what was truly inspiring was not the jobs, but the portraits. The book could have been called Families Who Vacation in Station Wagons or The Staff of Tombstone Arizona’s OK Corral Recreationists or Seven Cult Leaders of Castroville and I would have been equally enthralled. It’s not work that inspires me, necessarily, but life. Capturing life.

And I think this is the real lesson I found out on the road – that while working offers many of the same senses of security and stability as it always has, the path one takes to find it is much looser and organic. The people I talked to weren’t climbing. They weren’t delaying senses of self or identity until some future date. I might say, they were actually quite a bit happier than the portraits I discovered in Terkel’s book. I wasn’t expecting that. But it gives me something to strive for in my own work.