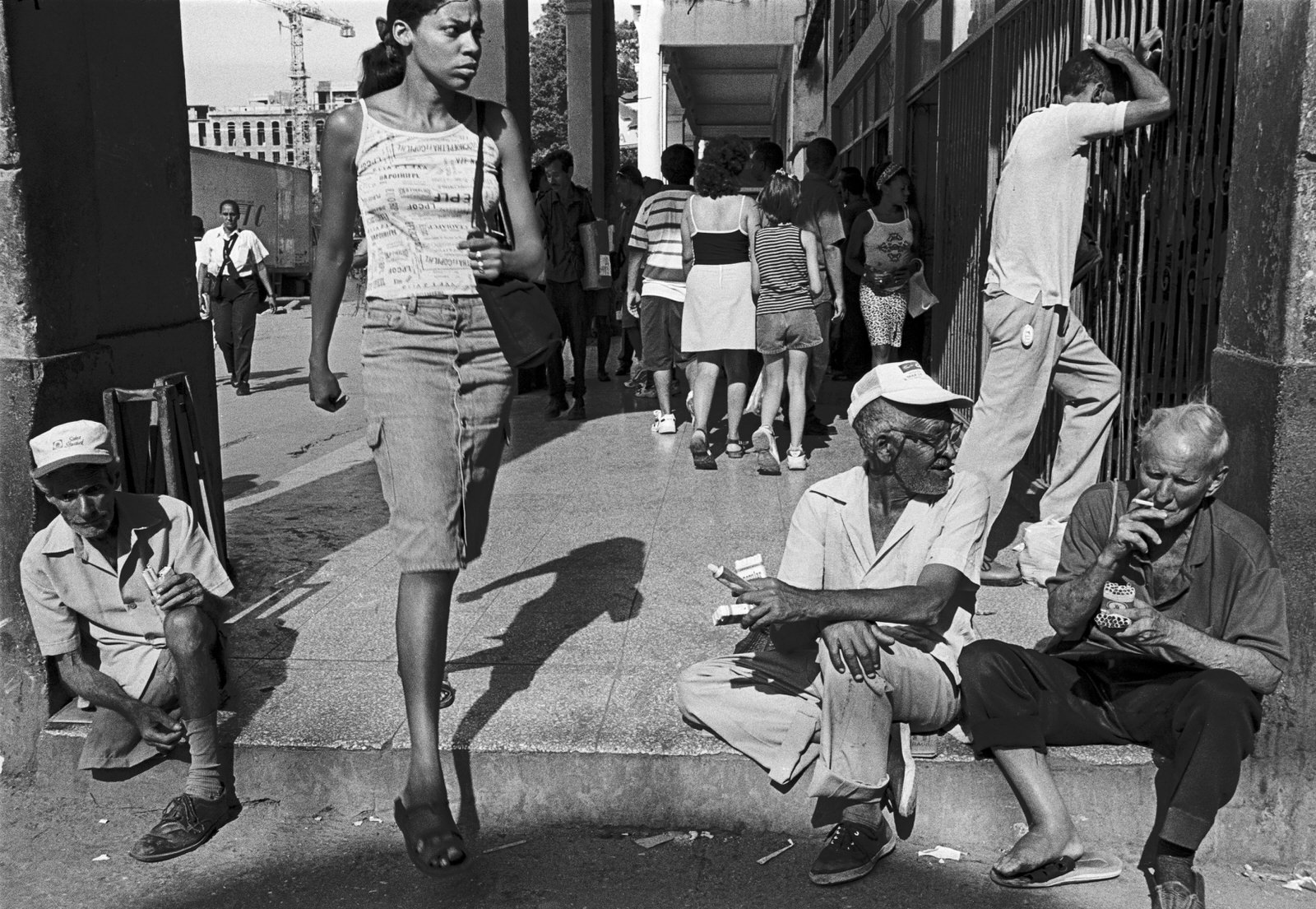

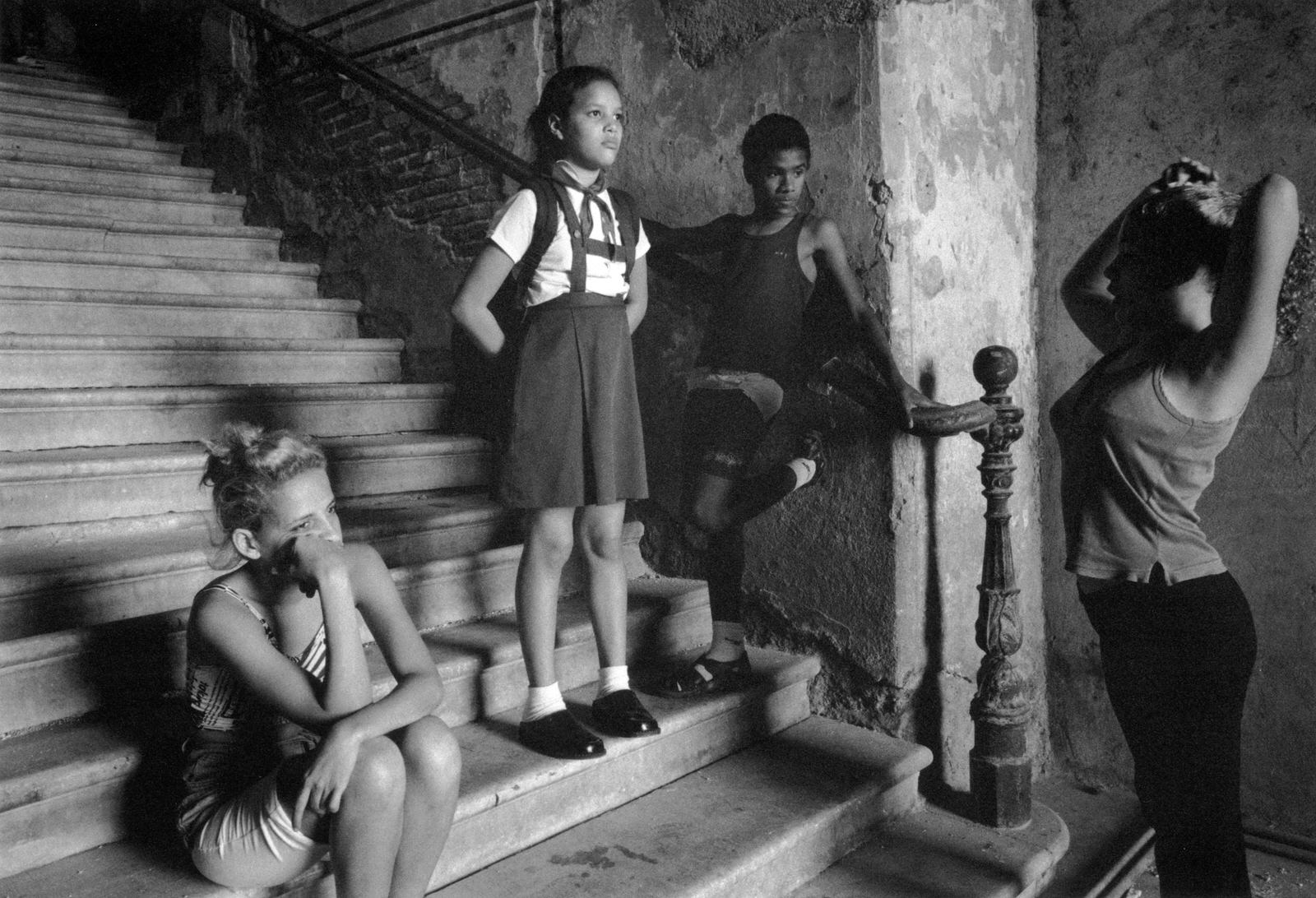

Beautiful and Raw Portraits of Real Cuba Over 10 Years by Susan S. Bank

Between 1999 and 2009, Susan S. Bank traveled to Cuba about 25 times, photographing the daily life of cubanos in Havana city and local tobacco farmers and their families in the Valley of Vinales in rural Pinar del Rio. Her first monograph, “Cuba: Campo Adentro” was published in 2008 and named one of “The Best Photography Books of the Year” by PHotoEspaña 2009 and “Best Books of the Year 2009” by Photo-eye Books.

Susan’s second monograph, “Piercing the Darkness” received first place in the 2016 Lucie Awards non-professional monograph category and selected pieces have been on display at numerous exhibitions in Cuba and the U.S.

I recently had the pleasure of talking to Susan about her work in Cuba and the powerful, raw portraits she took of the people she met, lived with, and thought of as family. Her images are captivating, and what’s truly inspiring is that Susan didn’t even begin her photography career until she was 60 years old. Since then, her black and white street photography has been featured in some of the biggest photography publications around, she’s spoken at a number of events, she continues to show her work in exhibitions and galleries, and she’s marketing her second book.

How did Cuba come about? You spent 10 years going back and forth, photographing Havana and el campo, why did you go to Cuba in the first place?

That’s a good question. I had been photographing in Mexico for quite a few years, but not as a very skilled photographer, and I was on my own, essentially. I knew very little about Cuba and I decided I wanted to go there partly because we’re not allowed to go there. I mean, U.S. citizens can go there, but they can’t spend money in Cuba.

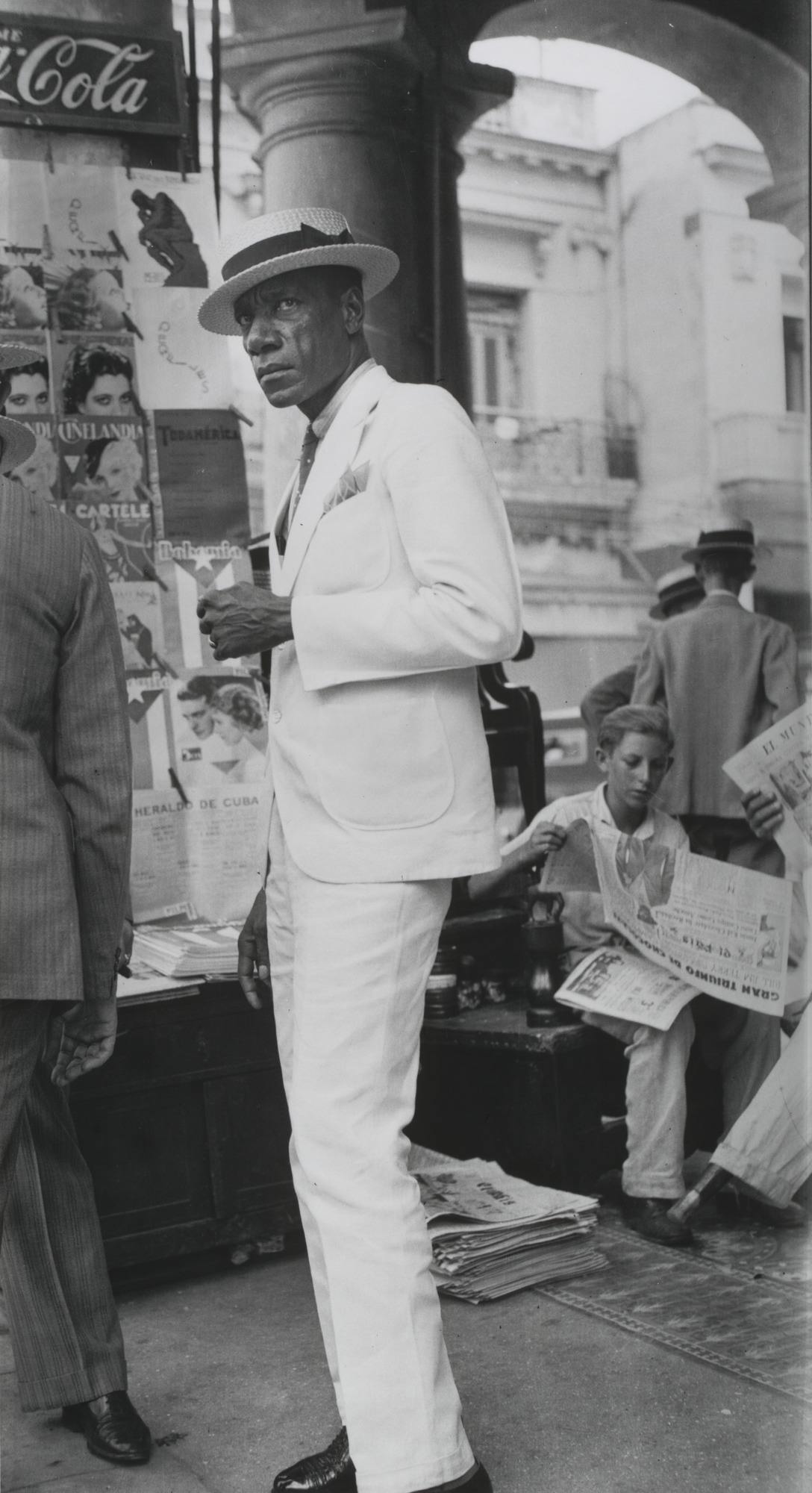

I knew very little about Cuba except for that wonderful “Walker Evans: Havana 1933.” So I went looking for Walker Evans in Havana, essentially. I applied independently for a license in 1998 and I was turned down. And I heard that the main photographic workshops were having their first workshop in Havana in October of ’99, so I signed up, and I went along with their license.

I studied there with David Alan Harvey in 1999. He didn’t really teach us anything except how to use flash with a green or brown beer bottle. [Laughs] We mainly learned the ropes of how to get around Havana and not to talk about politics; that was at a time when you did not talk about politics. And I enjoyed it so much that I went the next year and took another class with Constantine Manos. He’s also a street photographer and my experience with him was extremely different. I kept going back, he was very encouraging.

When did you begin to consider yourself a photographer and artist?

I was about 60 years old and I took a photo workshop with Mary Ellen Mark for two years in Oaxaca, and then I was on my way. She was very, very encouraging. Graciela Iturbide from Mexico joined her workshop and I became friendly with her; she is one of my favorite Mexican photographers. Graciela very generously invited me to come to Mexico and said she would take me to the places where she really liked to photograph. And I can’t believe this, I was too shy to take her up on her offer.

You didn’t go?

No. I can’t believe it. As one of my mentors, Professor Ricardo Viera from Lehigh University, said, “Susan, you would have been famous if you’d gone with Graciela.” I really goofed.

But what would have happened then? Maybe then Havana and el campo wouldn’t have happened.

That’s true, that’s true.

What was life like before that? What were you doing before you took up photography?

Well, I was born in 1938 and I pretty much followed the path that many women took who grew up in the 40s and 50s. I graduated from Barnard College in New York and the University of Edinburgh. After I graduated from college, I made my way to San Francisco like so many young women aspired to, and soon got married and had kids. I never thought of going to graduate school then. I was following the plan for most women my age. I worked in all different kinds of ways. I was a community organizer, I used to sell used homes, and I taught. Nothing very unusual for my age group. I was very involved with politics in the 60s, marches to Washington.

With a camera, I was a snapshot shooter, you know. I started taking snapshots when I was 10. I always enjoyed taking snapshots and my favorite photography books are actually family photograph albums. I am a collector of photography books but, still, my favorite ones are my family snapshot books.

What was it that drew you to the arts, to photography specifically? Were you always passionate about it?

No, no. It was my introduction through Mary Ellen Mark and Graciela that really changed me.

You said the Walker Evans photo, “Man in White Suit, Havana 1933″ inspired you to go to Cuba. What are some other artists, photographers that you most admire? And how have they influenced your work?

There are many, it’s very hard to answer. There’s no question that I like the work of Robert Frank. I think I have almost all of his books. Also, I like Josef Koudelka, especially his Exiles.

One of my favorite street photographers is from Havana, his name is Raul Canibano. I really admire him as a street photographer. I also really like Bruce Davidson. I like his method and he gives marvelous talks. He had a wonderful gimmick, a great trick. He used to carry in his pocket a little 5×7 wedding album. And in it he would put pictures that he had taken so when he approached new people he would say, “Look, this is what I do.” And it broke the ice for him.

That’s interesting because a lot of street photographers find it difficult, they struggle with approaching strangers. You mentioned in the School of Visual Arts talk that you did that you’ll bring things to the people you’re photographing, things that they need. You would bring food or photos to them. In one case you mentioned you brought Viagra to someone.

Right, to the father of a Cuban friend of mine. He didn’t last very long because his brother stole half of it!

One time a friend sent me a five-pound bag of costume jewelry. I took it with me and if I was developing a relationship with someone, the jewelry came out. It wasn’t really a form of payment, it was really a form of gratitude. In the case of my working in el campo, in the valley, for several years, I always brought them proofs, black and white proofs, and they were kind of shocked that they were black and white. They imagined the photographs would be in color.

Each time I went, I brought a box of 8×10 proofs and gave them out. And after my “Cuba: Campo Adentro” book was published in 2008, I was able to go in 2009 and I brought a book to all of the families – not easy to do because Cuban customs can be very strict with written materials coming in. I couldn’t put them all together in one box, or space or one suitcase. I sort of hid them among clothes and such. I can’t describe the joy that the campesinos felt when they opened the box. They’re highly, highly cherished.

Did you ever have an issue going up to strangers and asking to take their picture?

The campesinos were particularly challenging. For the most part, they didn’t have any photographs of themselves. One man had what looked like a school photograph but they were not familiar with photographs at all. I established right away that I was a photographer, that was something from Mary Ellen Mark, “Don’t fool around. Tell them right up front you are a photographer and that’s what you’re doing. Don’t do too much chitchat, just keep working. Establish yourself as a working photographer as soon as you can.”

In el campo, the challenge was they were not really sure what I was doing. It took quite a while to build trust. The matriarch of the valley, whose name was Martha and she had 10 adult children who were all born in the house where she lived, had to become comfortable with me. Eventually, it happened after two or three trips. She was pretty suspicious at first. But then when I started bringing pictures back they kind of understood.

One of the oldest farmers said to me one day, “Why are you taking pictures here? We are very poor. This is an ugly place.” He said, “There are so many places of beauty in the world, why are you here?” And I told him, “Wait till I come back on the next trip and I will give you my answer.” And I brought him a beautiful photograph of him on the caminito early in the morning with the light on the birds. It was a beautiful, beautiful photograph. I gave it to him and he smiled and he understood why I was there.

There’s so much beauty in your imagery, in the poverty and that life. It’s something that we don’t see a lot and I think you’re doing a great job of capturing it and showing it.

Hopefully, respectfully. Hopefully, my work comes off as being respectful.

How do you see these photos? And what is it that you’re trying to do when you’re shooting?

I think, and I’ve said this a lot of times, that what you do really has a lot to do with your DNA. I grew up poor but had an extremely rich life, especially in terms of community, and I sort of translated that to this valley, those feelings.

When you’re just shooting on the street and photographing strangers, what kind of strategies do you have to approach them?

I work by instinct. Sometimes I ask permission but most the time I don’t. If I sense that somebody is uncomfortable I just walk away. I don’t try to negotiate with them. I have an advantage, you know, I have gray hair, I’m short, overweight, carry one small camera and wear orthopedic type shoes, so I don’t think I’m very threatening!

On a typical day out shooting, do you have any habits that are part of your creative process?

Well, I’ll speak regarding the Cuba work. I used to shoot, take pictures late. In Cuba, I completely did a switch around, I started working very early in the morning. I’d wake up at 5:00 and be out on the streets at dawn. And often, and it was true in el campo and also true in Havana, I’m a repeat explorer. I continue to go back to the same places over and over again. You know, the lighting changes, the activity on the street changes. It’s never the same. The light is so challenging in Cuba. You don’t have many windows in which you can work unless you stay in the shadows.

Eventually I became very well known on the streets of central Havana. I was recognized by a lot of people and so I felt comfortable. I felt at home.

You’re building relationships with the people that you’re photographing.

For the most part, yes. Not everybody in Havana who is in my book, but many of them.

That adds a whole other aspect of intimacy because now you are essentially friends with the people you’re meeting. What did you take away from the experience?

It was a very rich experience for me. In el campo, I developed this fantasy that I was part of their family, which was not true, but I loved to imagine I was part of the family!

The last night I was in el campo in November 2009, I was saying goodbye to everybody and I was delivering my last book. They had a new sheriff in the valley and he drove this very expensive new motorcycle. I’m walking with a couple whom I’m very familiar with, I had just given them the book, and this new sheriff decided he needed to make his presence known. Fortunately, the family hid the book, they didn’t show it. That would have caused a big problem. The sheriff took my passport, he asked me a lot of questions. I just speak basic Spanish, but I knew enough to know what was going on at the time. He sort of detained me for about an hour. I wasn’t upset because I knew he couldn’t arrest me for anything.

When he left, the buzz spread through the valley like lightning. He actually went house to house, he drove his motorcycle house to house and asked everybody who I was. The woman I was staying with in the farmhouse, as I approached that place, all her shutters were closed. I approached the door and she pulled me inside very quickly. At that time, the campesinos said to me, “Oh, Susan, if you get in trouble we’re gonna back you up.” Well, I would like to believe that, but I doubt it!

What would have happened if he had known that you had done this book?

I expect he would have taken the book away because it showed pictures of the reality of that place, which I’m sure the government really doesn’t want people to know this. I think it was a form of harassment. I’d been harassed in the city before by police.

I did not realize this during the whole time I worked in el campo – and I’d go three, four times a year and spend a few weeks at a time – I did not know this at the time, but I was being followed by the authorities who had no uniforms on and they were riding bicycles. They could not understand why this woman kept returning to this place.

You stayed at the farm with the workers?

Yes, I did. They have a resort built by the Cubans for their short vacations, it’s really a dump, I would say. They have 10 rooms reserved for people like me, outsiders, and the rest of the little huts in these other buildings are reserved for Cuban vacationers. The difference between the two places is astounding.

It’s called “Campismo.” I would sign up there, I’d pay my little fee and maybe leave a few little things in my room. And then at 11 o’clock at night, people would come by with this horse and put all this luggage on the horse and take me to Ana’s house where I stayed. I was more ready to work early if I stayed in her house.

When you went there, did you already have the book in mind?

I never considered a book. I had a very nice exhibition in 2004 at the Fototeca in Havana, which is the main photography center in all of Cuba. When I came back, I showed my mentor, Ricardo Viera, from Lehigh University. He’s a Cuban-American and has an amazing collection of Latin-American photography in the university. I showed him my portfolio and right away he said, “This is a book.” And I said, “Really?” I had no design, and this was only in 2004 so I continued working there and added works that I wanted to be in the book.

The whole process was very interesting. I self-published my first one and I loved the control. The designer had never designed a book before, I had never done a book before. The second book, the Havana book, was a very, very different experience. I had, I think, three publishers who wanted to publish the book. The company that printed my first book offered to publish the second book, “Piercing the Darkness.” It was a very different experience. I still have a lot of control. The problem in publishing a book is that the author can easily lose control. I am pretty particular, so I was able to keep control with both books.

The campo book was unusual because at that point nobody had done a monograph on life in the Cuban countryside. You know Ernesto Bazan? He worked a lot on el campo and after a certain time he published a book on it. It was different because it was in color and he worked in a different valley. With Havana, so many books have been published about Havana. Absolute overload.

What do you do when you hit a creative block? How do you deal with that?

I certainly have had them, I’d say in the last three or four years. Sometimes I just have to retreat. I don’t feel like engaging, I want to be alone. So what I’ve been doing in the last couple years is photographing things that are close to where I live in the summer. Living in New England, fortunately, we have a good climate for four months. It’s a place that means a lot to me. I’ve just been taking pictures very, very close to where I live, including trees and rock.

And next, in my studio, I have at least 20 good sized boxes full of materials for making artists books. At least 20 boxes. Stuff that I’ve collected. I even have a holster for a Nazi World War II pistol; I want to do something with that. I also want to do something with my mother’s suitcase with her initials on it, as a book. I know how I would construct it, but I haven’t gotten there yet. I have ideas of things that I really, really want to do. I’m interested also in collage, working with different materials and with photographs.

Do you have a favorite quote that gets you fired up? A quote or a mantra that you tell yourself.

Well, when I’m working, two people, two teachers, one over each shoulder. Mary Ellen Mark is yelling over my left shoulder, and I mean really yelling, “Get the picture. Get the picture.” She doesn’t care if the setup is perfect, if the lighting is perfect, or anything like that. “Get the picture.” On my right shoulder is Constantine Manos, who is so different and has so many rules. And Consta is telling me, “Get the perfect picture.” I can never satisfy Consta. He will come to an exhibition that I have and he’ll look at the prints on the wall and he’ll have his hands behind his back and say, “Oh, Susan, what a pity.” [Laughs] It doesn’t upset me.

Do you have a favorite photo of yours?

I have a lot of favorite photos. That question is very difficult for me to answer. One that I really like is the picture of the Havana dogs on the street. I like that picture because to me it’s the best metaphor for life for Habaneros in Havana. That picture’s been censored, I couldn’t put it in certain shows.

Do you have a book that you like to recommend to other creative people?

Oh, so many books. I have a pretty good book collection. I didn’t start collecting books until maybe 10 years ago. I didn’t want to be influenced by other photographers’ work; I sort of backed away from that. One of my favorite photographers who’s a master printer and a master of light and shadow is a Cuban-American who lives in Miami and his name is Mario Algaze. He has several books. A very complicated man. One of the masters.

You mentioned that you’d been to Cuba 25 times between ’99 and 2009, have you been back since?

No, not since 2009. No. I doubt if I’ll go back. I think it’s too painful.

What have you been working on since?

I’ve been really pushing very hard to market the second book, “Piercing the Darkness.” The publisher does not have a distributor, so I’ve been doing a lot of legwork with that, so I would say I’m in transition. We have to get this book out of my system and move on.

I’m having, I think, what should be a very interesting exhibition this summer at the Leica Gallery in Boston. It’s called “Cuba: Piercing the Darkness.” The opening is July 12th and it runs until September 9th.

And I’m about to jump into the pool and purchase a digital camera. I don’t own one yet. I’m still working on it! I hope by the end of this summer, in 2018, I’ll have a digital camera!

If you would like to see more of Susan’s work, including her Mexico and Salisbury Beach series, check out her website. And, if you’re in the Boston area this summer, be sure to stop by her exhibition at the Leica Gallery! Once you’re there, if you see Susan, I’d definitely suggest you say hello, her storytelling and infectious laugh are as captivating as her images!